|

| Accueil |

Créer un blog |

Accès membres |

Tous les blogs |

Meetic 3 jours gratuit |

Meetic Affinity 3 jours gratuit |

Rainbow's Lips |

Badoo |

[ Economie ] [ Philosophie ] [ Commerce. ] [ Kant ] [ Hegel ] [ ASp ] [ C ] [ Micro-economique ] [ Macro-economie ] [ Social ] [ Emploi ] [ Aristote ]

|

|

|

|

!?Revolution!?

16/11/2012 14:14

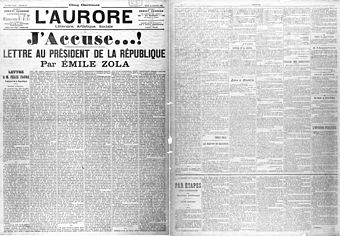

LETTER TO THE PRESIDENT OF THE REPUBLIC

The text of the letter, as published in L'Aurore

Letter to Mr. Félix Faure,

President of the Republic

Mr. President,

Would you allow me, in my gratitude for the benevolent reception that you gave me one day, to draw the attention of your rightful glory and to tell you that your star, so happy until now, is threatened by the most shameful and most ineffaceable of blemishes?

You have passed healthy and safe through base calumnies; you have conquered hearts. You appear radiant in the apotheosis of this patriotic festival that the Russian alliance was for France, and you prepare to preside over the solemn triumph of our World Fair, which will crown our great century of work, truth and freedom. But what a spot of mud on your nameâ—âI was going to say on your reignâ—âis this abominable Dreyfus affair! A council of war, under order, has just dared to acquit Esterhazy, a great blow to all truth, all justice. And it is finished, France has this stain on her cheek, History will write that it was under your presidency that such a social crime could be committed.

Since they dared, I too will dare. The truth I will say, because I promised to say it, if justice, regularly seized, did not do it, full and whole. My duty is to speak, I do not want to be an accomplice. My nights would be haunted by the specter of innocence that suffer there, through the most dreadful of tortures, for a crime it did not commit.

And it is to you, Mr. President, that I will proclaim it, this truth, with all the force of the revulsion of an honest man. For your honor, I am convinced that you are unaware of it. And with whom will I thus denounce the criminal foundation of these guilty truths, if not with you, the first magistrate of the country?

∴

First, the truth about the lawsuit and the judgment of Dreyfus.

A nefarious man carried it all out, did everything: Lieutenant Colonel Du Paty de Clam, at that time only a Commandant. He is the entirety of the Dreyfus business; it will be known only when one honest investigation clearly establishes his acts and responsibilities. He seems a most complicated and hazy spirit, haunting romantic intrigues, caught up in serialized stories, stolen papers, anonymous letters, appointments in deserted places, mysterious women who sell condemning evidences at night. It is he who imagined dictating the Dreyfus memo; it is he who dreamed to study it in an entirely hidden way, under ice; it is him whom commander Forzinetti describes to us as armed with a dark lantern, wanting to approach the sleeping defendant, to flood his face abruptly with light and to thus surprise his crime, in the agitation of being roused. And I need hardly say that that what one seeks, one will find. I declare simply that commander Du Paty de Clam, charged to investigate the Dreyfus business as a legal officer, is, in date and in responsibility, the first culprit in the appalling miscarriage of justice committed.

The memo was for some time already in the hands of Colonel Sandherr, director of the office of information, who has since died of general paresis. "Escapes" took place, papers disappeared, as they still do today; the author of the memo was sought, when ahead of time one was made aware, little by little, that this author could be only an officer of the High Comman and an artillery officer: a doubly glaring error, showing with which superficial spirit this affair had been studied, because a reasoned examination shows that it could only be a question of an officer of troops. Thus searching the house, examining writings, it was like a family matter, a traitor to be surprised in the same offices, in order to expel him. And, while I don't want to retell a partly known history here, Commander Paty de Clam enters the scene, as soon as first suspicion falls upon Dreyfus. From this moment, it is he who invented Dreyfus, the affair becomes that affair, made actively to confuse the traitor, to bring him to a full confession. There is the Minister of War, General Mercier, whose intelligence seems poor; there are the head of the High Command, General De Boisdeffre, who appears to have yielded to his clerical passion, and the assistant manager of the High Command, General Gonse, whose conscience could put up with many things. But, at the bottom, there is initially only Commander Du Paty de Clam, who carries them all out, who hypnotizes them, because he deals also with spiritism, with occultism, conversing with spirits. One could not conceive of the experiments to which he subjected unhappy Dreyfus, the traps into which he wanted to make him fall, the insane investigations, monstrous imaginations, a whole torturing insanity.

Ah! this first affair is a nightmare for those who know its true details! Commander Du Paty de Clam arrests Dreyfus, in secret. He turns to Mrs. Dreyfus, terrorizes her, says to her that, if she speaks, her husband is lost. During this time, the unhappy one tore his flesh, howled his innocence. And the instructions were made thus, as in a 15th century tale, shrouded in mystery, with a savage complication of circumstances, all based on only one childish charge, this idiotic affair, which was not only a vulgar treason, but was also the most impudent of hoaxes, because the famously delivered secrets were almost all without value. If I insist, it is that the kernel is here, from whence the true crime will later emerge, the terrible denial of justice from which France is sick. I would like to touch with a finger on how this miscarriage of justice could be possible, how it was born from the machinations of Commander Du Paty de Clam, how General Mercier, General De Boisdeffre and General Gonse could be let it happen, to engage little by little their responsibility in this error, that they believed a need, later, to impose like the holy truth, a truth which is not even discussed. At the beginning, there is not this, on their part, this incuriosity and obtuseness. At most, one feels them to yield to an ambiance of religious passions and the prejudices of the physical spirit. They allowed themselves a mistake.

But here Dreyfus is before the council of war. Closed doors are absolutely required. A traitor would have opened the border with the enemy to lead the German emperor to Notre-Dame, without taking measures to maintain narrow silence and mystery. The nation is struck into a stupor, whispering of terrible facts, monstrous treasons which make History indignant; naturally the nation is so inclined. There is no punishment too severe, it will applaud public degradation, it will want the culprit to remain on his rock of infamy, devoured by remorse. Is this then true, the inexpressible things, the dangerous things, capable of plunging Europe into flames, which one must carefully bury behind these closed doors? No! There was behind this, only the romantic and lunatic imaginations of Commander Paty de Clam. All that was done only to hide the most absurd of novella plots. And it suffices, to ensure oneself of this, to study with attention the bill of indictment, read in front of the council of war.

Ah! the nothingness of this bill of indictment! That a man could be condemned for this act, is a wonder of iniquity. I defy decent people to read it, without their hearts leaping in indignation and shouting their revolt, while thinking of the unwarranted suffering, over there, on Devil's Island. Dreyfus knows several languages, crime; one found at his place no compromising papers, crime; he returns sometimes to his country of origin, crime; he is industrious, he wants to know everything, crime; he is unperturbed, crime; he is perturbed, crime. And the naiveté of drafting formal assertions in a vacuum! One spoke to us of fourteen charges: we find only one in the final analysis, that of the memo; and we even learn that the experts did not agree, than one of them, Mr. Gobert, was coerced militarily, because he did not allow himself to reach a conclusion in the desired direction. One also spoke of twenty-three officers who had come to overpower Dreyfus with their testimonies. We remain unaware of their interrogations, but it is certain that they did not all charge him; and it is to be noticed, moreover, that all belonged to the war offices. It is a family lawsuit, one is there against oneself, and it is necessary to remember this: the High Command wanted the lawsuit, it was judged, and it has just judged it a second time.

Therefore, there remained only the memo, on which the experts had not concurred. It is reported that, in the room of the council, the judges were naturally going to acquit. And consequently, as one includes/understands the despaired obstinacy with which, to justify the judgment, today the existence of a secret part is affirmed, overpowering, the part which cannot be shown, which legitimates all, in front of which we must incline ourselves, the good invisible and unknowable God! I deny it, this part, I deny it with all my strength! A ridiculous part, yes, perhaps the part wherein it is a question of young women, and where a certain D… is spoken of which becomes too demanding: some husband undoubtedly finding that his wife did not pay him dearly enough. But a part interesting the national defense, which one could not produce without war being declared tomorrow, no, no! It is a lie! and it is all the more odious and cynical that they lie with impunity without one being able to convince others of it. They assemble France, they hide behind its legitimate emotion, they close mouths by disturbing hearts, by perverting spirits. I do not know a greater civic crime.

Here then, Mr. President, are the facts which explain how a miscarriage of justice could be made; and the moral evidence, the financial circumstances of Dreyfus, the absence of reason, his continual cry of innocence, completes its demonstration as a victim of the extraordinary imaginations of commander Du Paty de Clam, of the clerical medium in which it was found, of the hunting for the "dirty Jews", which dishonours our time.

∴

And we arrive at the Esterhazy affair. Three years passed, many consciences remain deeply disturbed, worry, seek, end up being convinced of Dreyfus's innocence.

I will not give the history of the doubts and of the conviction of Mr. Scheurer-Kestner. But, while this was excavated on the side, it ignored serious events among the High Command. Colonel Sandherr was dead, and Major Picquart succeeded him as head of the office of the information. And it was for this reason, in the performance of his duties, that the latter one day found in his hands a letter-telegram, addressed to commander Esterhazy, from an agent of a foreign power. His strict duty was to open an investigation. It is certain that he never acted apart from the will of his superiors. He thus submitted his suspicions to his seniors in rank, General Gonse, then General De Boisdeffre, then General Billot, who had succeeded General Mercier as the Minister of War. The infamous Picquart file, about which so much was said, was never more than a Billot file, a file made by a subordinate for his minister, a file which must still exist within the Ministry of War. Investigations ran from May to September 1896, and what should be well affirmed is that General Gonse was convinced of Esterhazy's guilt, and that Generals De Boisdeffre and Billot did not question that the memo was written by Esterhazy. Major Picquart's investigation had led to this unquestionable observation. But the agitation was large, because the condemnation of Esterhazy inevitably involved the revision of Dreyfus's trial; and this, the High Command did not want at any cost.

There must have been a minute full of psychological anguish. Notice that General Billot was in no way compromised, he arrived completely fresh, he could decide the truth. He did not dare, undoubtedly in fear of public opinion, certainly also in fear of betraying all the High Command, General De Boisdeffre, General Gonse, not mentioning those of lower rank. Therefore there was only one minute of conflict between his conscience and what he believed to be the military's interest. Once this minute had passed, it was already too late. He had engaged, he was compromised. And, since then, his responsibility only grew, he took responsibility for the crimes of others, he became as guilty as the others, he was guiltier than them, because he was the Master of justice, and he did nothing. Understand that! Here for a year General Billot, General De Boisdeffre and General Gonse have known that Dreyfus is innocent, and they kept this appalling thing to themselves! And these people sleep at night, and they have women and children whom they love!

Major Picquart had fulfilled his duty as an honest man. He insisted to his superiors, in the name of justice. He even begged them, he said to them how much their times were ill-advised, in front of the terrible storm which was to pour down, which was to burst, when the truth would be known. It was, later, the language that Mr. Scheurer-Kestner also used with General Billot, entreating him with patriotism to take the affair in hand, not to let it worsen, on the verge of becoming a public disaster. No! The crime had been committed, the High Command could no longer acknowledge its crime. And Major Picquart was sent on a mission, one that took him farther and farther away, as far as Tunisia, where there was not even a day to honour his bravery, charged with a mission which would have surely ended in massacre, in the frontiers where Marquis de Morès met his death. He was not in disgrace, General Gonse maintained a friendly correspondence with him. It is only about secrets he was not good to have discovered.

To Paris, the truth inexorably marched, and it is known how the awaited storm burst. Mr. Mathieu Dreyfus denounced commander Esterhazy as the true author of the memo just as Mr. Scheurer-Kestner demanded a revision of the case to the Minister of Justice. And it is here that commander Esterhazy appears. Testimony shows him initially thrown into a panic, ready for suicide or escape. Then, at a blow, he acted with audacity, astonishing Paris by the violence of his attitude. It is then that help had come to him, he had received an anonymous letter informing him of the work of his enemies, a mysterious lady had come under cover of night to return a stolen evidence against him to the High Command, which would save him. And I cannot help but find Major Paty de Clam here, considering his fertile imagination. His work, Dreyfus's culpability, was in danger, and he surely wanted to defend his work. The retrial was the collapse of such an extravagant novella, so tragic, whose abominable outcome takes place in Devil's Island! This is what he could not allow. Consequently, a duel would take place between Major Picquart and Major Du Paty de Clam, one with face uncovered, the other masked. They will soon both be found before civil justice. In the end, it was always the High Command that defended itself, that did not want to acknowledge its crime; the abomination grew hour by hour.

One wondered with astonishment who were protecting commander Esterhazy. It was initially, in the shadows, Major Du Paty de Clam who conspired all and conducted all. His hand was betrayed by its absurd means. Then, it was General De Boisdeffre, it was General Gonse, it was General Billot himself, who were obliged to discharge the commander, since they cannot allow recognition of Dreyfus's innocence without the department of war collapsing under public contempt. And the beautiful result of this extraordinary situation is that the honest man there, Major Picquart, who only did his duty, became the victim of ridicule and punishment. O justice, what dreadful despair grips the heart! One might just as well say that he was the forger, that he manufactured the carte-télegramme to convict Esterhazy. But, good God! why? with what aim? give a motive. Is he also paid by the Jews? The joke of the story is that he was in fact an anti-Semite. Yes! we attend this infamous spectacle, of the lost men of debts and crimes upon whom one proclaims innocence, while one attacks honor, a man with a spotless life! When a society does this, it falls into decay.

Here is thus, Mr. President, the Esterhazy affair: a culprit whose name it was a question of clearing. For almost two months, we have been able to follow hour by hour the beautiful work. I abbreviate, because it is not here that a summary of the history's extensive pages will one day be written out in full. We thus saw General De Pellieux, then the commander of Ravary, lead an investigation in which the rascals are transfigured and decent people are dirtied. Then, the council of war was convened.

∴

How could one hope that a council of war would demolish what a council of war had done?

I do not even mention the always possible choice of judges. Isn't the higher idea of discipline, which is in the blood of these soldiers, enough to cancel their capacity for equity? Who says discipline breeds obedience? When the Minister of War, the overall chief, established publicly, with the acclamations of the national representation, the authority of the final decision; you want a council of war to give him a formal denial? Hierarchically, that is impossible. General Billot influenced the judges by his declaration, and they judged as they must under fire, without reasoning. The preconceived opinion that they brought to their seats, is obviously this one: "Dreyfus was condemned for crime of treason by a council of war, he is thus guilty; and we, a council of war, cannot declare him innocent, for we know that to recognize Esterhazy's guilt would be to proclaim the innocence of Dreyfus." Nothing could make them leave that position.

They delivered an iniquitous sentence that will forever weigh on our councils of war, sullying all their arrests from now with suspicion. The first council of war could have been foolish; the second was inevitably criminal. Its excuse, I repeat it, was that the supreme chief had spoken, declaring the thing considered to be unassailable, holy and higher than men, so that inferiors could not say the opposite. One speaks to us about the honor of the army, that we should like it, respect it. Ah! admittedly, yes, the army which would rise to the first threat, which would defend the French ground, it is all the people, and we have for it only tenderness and respect. But it is not a question of that, for which we precisely want dignity, in our need for justice. It is about the sword, the Master that one will give us tomorrow perhaps. And do not kiss devotedly the handle of the sword, by god!

I have shown in addition: the Dreyfus affair was the affair of the department of war, a High Command officer, denounced by his comrades of the High Command, condemned under the pressure of the heads of the High Command. Once again, it cannot restore his innocence without all the High Command being guilty. Also the offices, by all conceivable means, by press campaigns, by communications, by influences, protected Esterhazy only to convict Dreyfus a second time. What sweeping changes should the republican government should give to this [Jesuitery], as General Billot himself calls it! Where is the truly strong ministry of wise patriotism that will dare to reforge and to renew all? What of people I know who, faced with the possibility of war, tremble of anguish knowing in what hands lies national defense! And what a nest of base intrigues, gossips and dilapidations has this crowned asylum become, where the fate of fatherland is decided! One trembles in face of the terrible day that there has just thrown the Dreyfus affair, this human sacrifice of an unfortunate, a "dirty Jew"! Ah! all that was agitated insanity there and stupidity, imaginations insane, practices of low police force, manners of inquisition and tyranny, good pleasure of some non-commissioned officers putting their boots on the nation, returning in its throat its cry of truth and justice, under the lying pretext and sacrilege of the reason of State.

And it is a yet another crime to have [pressed on ?] the filthy press, to have let itself defend by all the rabble of Paris, so that the rabble triumphs insolently in defeat of law and simple probity. It is a crime to have accused those who wished for a noble France, at the head of free and just nations, of troubling her, when one warps oneself the impudent plot to impose the error, in front of the whole world. It is a crime to mislay the opinion, to use for a spiteful work this opinion, perverted to the point of becoming delirious. It is a crime to poison the small and the humble, to exasperate passions of reaction and intolerance, while taking shelter behind the odious antisemitism, from which, if not cured, the great liberal France of humans rights will die. It is a crime to exploit patriotism for works of hatred, and it is a crime, finally, to turn into to sabre the modern god, when all the social science is with work for the nearest work of truth and justice.

This truth, this justice, that we so passionately wanted, what a distress to see them thus souffletées, more ignored and more darkened! I suspect the collapse which must take place in the heart of Mr. Scheurer-Kestner, and I believe well that he will end up feeling remorse for not having acted revolutionarily, the day of questioning at the Senate, by releasing all the package, [for all to throw to bottom]. He was the great honest man, the man of his honest life, he believed that the truth sufficed for itself, especially when it seemed as bright as the full day. What good is to turn all upside down when the sun was soon to shine? And it is for this trustful neutrality for which he is so cruelly punished. The same for Major Picquart, who, for a feeling of high dignity, did not want to publish the letters of General Gonse. These scruples honour it more especially as, while there remained respectful discipline, its superiors covered it with mud, informed themselves its lawsuit, in the most unexpected and outrageous manner. There are two victims, two good people, two simple hearts, who waited for God while the devil acted. And one even saw, for Major Picquart, this wretched thing: a French court, after having let the rapporteur charge a witness publicly, to show it of all the faults, made the closed door, when this witness was introduced to be explained and defend himself. I say that this is another crime and that this crime will stir up universal conscience. Decidedly, the military tribunals have a singular idea of justice.

Such is thus the simple truth, Mr. President, and it is appalling, it will remain a stain for your presidency. I very much doubt that you have no capacity in this affair, that you are the prisoner of the Constitution and your entourage. You do not have of them less one to have of man, about which you will think, and which you will fulfill. It is not, moreover, which I despair less of the world of the triumph. I repeat it with a more vehement certainty: the truth marches on and nothing will stop it. Today, the affair merely starts, since today only the positions are clear: on the one hand, the culprits who do not want the light to come; the other, the carriers of justice who will give their life to see it come. I said it elsewhere, and I repeat it here: when one locks up the truth under ground, it piles up there, it takes there a force such of explosion, that, the day when it bursts, it makes everything leap out with it. We will see, if we do not prepare for later, the most resounding of disasters.

But this letter is long, Mr. President, and it is time to conclude.

I accuse Major Du Paty de Clam as the diabolic workman of the miscarriage of justice, without knowing, I have wanted to believe it, and of then defending his harmful work, for three years, by the guiltiest and most absurd of machinations.

I accuse General Mercier of being an accomplice, if by weakness of spirit, in one of greatest iniquities of the century.

I accuse General Billot of having held in his hands the unquestionable evidence of Dreyfus's innocence and of suppressing it, guilty of this crime that injures humanity and justice, with a political aim and to save the compromised Chie of High Command.

I accuse General De Boisdeffre and General Gonse as accomplices of the same crime, one undoubtedly by clerical passion, the other perhaps by this spirit of body which makes offices of the war an infallible archsaint.

I accuse General De Pellieux and commander Ravary of performing a rogue investigation, by which I mean an investigation of the most monstrous partiality, of which we have, in the report of the second, an imperishable monument of naive audacity.

I accuse the three handwriting experts, sirs Belhomme, Varinard and Couard, of submitting untrue and fraudulent reports, unless a medical examination declares them to be affected by a disease of sight and judgment.

I accuse the offices of the war of carrying out an abominable press campaign, particularly in the Flash and the Echo of Paris, to mislead the public and cover their fault.

Finally, I accuse the first council of war of violating the law by condemning a defendant with unrevealed evidence, and I accuse the second council of war of covering up this illegality, by order, by committing in his turn the legal crime of knowingly discharging the culprit.

While proclaiming these charges, I am not unaware of subjecting myself to articles 30 and 31 of the press law of July 29, 1881, which punishes the offense of slander. And it is voluntarily that I expose myself.

As for the people I accuse, I do not know them, I never saw them, I have against them neither resentment nor hatred. They are for me only entities, spirits of social evil. And the act I accomplished here is only a revolutionary mean for hastening the explosion of truth and justice.

I have only one passion, that of the light, in the name of humanity which has suffered so and is entitled to happiness. My ignited protest is nothing more than the cry of my heart. That one thus dares to translate for me into court bases and that the investigation takes place at the great day!

I am waiting.

Please accept, Mr. President, the assurance of my deep respect.

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sunspots and Lotteries

06/11/2012 11:55

Sunspots and Lotteries

organized by Edward C. Prescott and Karl Shell

Vol. 107, No. 1, November 2002

-

Introduction to Sunspots and Lotteries, Edward C. Prescott and Karl Shell pp. 1-10

-

Symposium Equilibrium Prices When the Sunspot Variable Is Continuous, Rod Garratt, Todd Keister, Cheng-Zhong Qin and Karl Shell pp. 11-38

-

Lotteries, Sunspots, and Incentive Constraints, Timothy J. Kehoe, David K. Levine and Edward C. Prescott pp. 39-69

General Equilibrium Approach to Economic Growth

organized by Christian Ghiglino

Vol. 105, No. 1, July 2002

-

Introduction to a General Equilibrium Approach to Economic Growth, Christian Ghiglino pp. 1-17

-

Factor Saving Innovation, Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine pp. 18-41

-

Equilibrium Welfare and Government Policy with Quasi-geometric Discounting, Per Krusell, Burhanettin Kuruscu and Anthony A.Smith, Jr. pp. 42-72

-

On Non-existence of Markov Equilibria in Competitive-Market Economies, Manuel S. Santos pp. 73-98

-

Equilibrium Dynamics in a Two-Sector Model with Taxes, Salvador Ortigueira and Manuel S. Santos pp. 99-119

-

Poverty Traps, Indeterminacy, and the Wealth Distribution, Christian Ghiglino and Gerhard Sorger pp. 120-139

-

Intersectoral Externalities and Indeterminacy, Kazuo Nishimura and Alain Venditti pp. 140-157

-

Optimal Growth Models with Bounded or Unbounded Returns: A Unifying Approach, Cuong Le Van and Lisa Morhaim pp. 158-187

-

Ramsey Equilibrium in a Two-Sector Model with Heterogeneous Households, Robert A. Becker and Eugene N. Tsyganov pp. 188-225

-

On the Long-Run Distribution of Capital in the Ramsey Model, Gerhard Sorger pp. 226-243

-

Trade and Indeterminacy in a Dynamic General Equilibrium Model, Kazuo Nishimura and Koji Shimomura pp. 244-260

Experimental Game Theory

organized by Vincent P. Crawford

Vol. 104, No. 1, May 2002

-

Introduction to Experimental Game Theory, Vincent P. Crawford pp. 1-15

-

Detecting Failures of Backward Induction: Monitoring Information Search in Sequential Bargaining, Eric J. Johnson, Colin Camerer, Sankar Sen and Talia Rymon pp. 16-47

-

A Backward Induction Experiment, Ken Binmore, John McCarthy, Giovanni Ponti, Larry Samuelson and Avner Shaked pp. 48-88

-

Implementation by Iterative Dominance and Backward Induction: An Experimental Comparison, Elena Katok, Martin Sefton and Abdullah Yavas pp. 89-103

-

A Suggested Interpretation of Some Experimental Results on Preplay Communication, Miguel A. Costa-Gomes pp. 104-136

-

Sophisticated Experience-Weighted Attraction Learning and Strategic Teaching in Repeated Games, Colin F. Camerer, Teck-Hua Ho and Juin-Kuan Chong pp. 137-188

-

Mixed Strategy Play and the Minimax Hypothesis, Jason M. Shachat pp. 189-226

-

Prudence, Justice, Benevolence, and Sex: Evidence from Similar Bargaining Games, John Van Huyck and Raymond Battalio pp. 227-246

-

Quantal Response Equilibrium and Overbidding in Private-Value Auctions, Jacob K. Goeree, Charles A. Holt and Thomas R. Palfrey pp. 247-272

Political Science

organized by David Austen-Smith, Jeffrey S. Banks and Aldo Rustichini

Vol. 103, No. 1, March 2002

-

Introduction to Political Science, David Austen-Smith, Jeffrey S. Banks and Aldo Rustichini pp. 1-10

-

Uniqueness of Stationary Equilibrium Payoffs in the Baron-Ferejohn Model, Hülya Eraslan pp. 11-30

-

Majority Rule in a Stochastic Model of Bargaining, Hülya Eraslan and Antonio Merlo pp. 31-48

-

Coalition and Party Formation in a Legislative Voting Game, Matthew O. Jackson and Boaz Moselle pp. 49-87

-

Bounds for Mixed Strategy Equilibria and the Spatial Model of Elections, Jeffrey S. Banks, John Duggan and Michel Le Breton pp. 88-105

-

Distributive Politics and Electoral Competition, Jean-François Laslier and Nathalie Picard pp. 106-130

-

Mixed Equilibrium in a Downsian Model with a Favored Candidate, Enriqueta Aragones and Thomas R. Palfrey pp. 131-161

-

Campaign Spending with Office-Seeking Politicians, Rational Voters, and Multiple Lobbies, Andrea Prat pp. 162-189

-

Voting by Successive Elimination and Strategic Candidacy, Bhaskar Dutta, Matthew O. Jackson and Michel Le Breton pp. 190-218

-

Comparison of Scoring Rules in Poisson Voting Games, Roger B. Myerson pp. 219-251

Repeated Games with Private Monitoring

organized by Michihiro Kandori

Vol. 102, No. 1, January 2002

-

Introduction to Repeated Games with Private Monitoring, Michihiro Kandori pp. 1-15

-

Moral Hazard and Private Monitoring, V. Bhaskar and Eric van Damme pp. 16-39

-

Belief-Based Equilibria in the Repeated Prisoners' Dilemma with Private Monitoring, V. Bhaskar and Ichiro Obara pp. 40-69

-

The Repeated Prisoner's Dilemma with Imperfect Private Monitoring, Michele Piccione pp. 70-83

-

A Robust Folk Theorem for the Prisoner's Dilemma, Jeffrey C. Ely and Juuso Välimäki pp. 84-105

-

On Sustaining Cooperation without Public Observations, Olivier Compte pp. 106-150

-

On Failing to Cooperate When Monitoring Is Private, Olivier Compte pp. 151-188

-

Repeated Games with Almost-Public Monitoring, George J. Mailath and Stephen Morris pp. 189-228

-

Collusion in Dynamic Bertrand Oligopoly with Correlated Private Signals and Communication, Masaki Aoyagi pp. 229-248

Monetary and Financial Arrangements

Vol. 99, No. 1/2, July/August 2001

-

Introduction to Monetary and Financial Arrangements, Bruce D. Smith pp. 1-21

-

Limited Commitment, Money, and Credit, Saqib Jafarey and Peter Rupert pp. 22-58

-

Private and Public Circulating Liabilities, Costas Azariadis, James Bullard and Bruce D. Smith pp. 59-116

-

Cigarette Money, Kenneth Burdett, Alberto Trejos and Randall Wright pp. 117-142

-

Dynamic Consequences of Stabilization Policies Based on a Return to a Gold Standard, Beatrix Paal pp. 143-186

-

Monetary Stability and Liquidity Crises: The Role of the Lender of Last Resort, Gaetano Antinolfi, Elisabeth Huybens and Todd Keister pp. 187-219

-

A Model of Financial Fragility, Roger Lagunoff and Stacey L. Schreft pp. 220-264

-

Volatile Policy and Private Information: The Case of Monetary Shocks, Larry E. Jones and Rodolfo E. Manuelli pp. 265-296

-

Payments Systems Design in Deterministic and Private Information Environments, Ted Temzelides and Stephen D. Williamson pp. 297-326

-

When Should Bank Regulation Favor the Wealthy?, Pere Gomis-Porqueras pp. 327-337

-

On Credible Monetary Policy and Private Government Information, Christopher Sleet pp. 338-376

Evolution of Preferences

organized by Larry Samuelson

Vol. 97, No. 2, April 2001

-

Introduction to the Evolution of Preferences, Larry Samuelson pp. 225-230

-

On the Evolution of Individualistic Preferences: An Incomplete Information Scenario, Efe A. Ok and Fernando Vega-Redondo pp. 231-254

-

Nash Equilibrium and the Evolution of Preferences, Jeffrey C. Ely and Okan Yilankaya pp. 255-272

-

Preference Evolution and Reciprocity, Rajiv Sethi and E. Somanathan pp. 273-297

-

The Economics of Cultural Transmission and the Dynamics of Preferences, Alberto Bisin and Thierry Verdier pp. 298-319

-

Analogies, Adaptation, and Anomalies, Larry Samuelson pp. 320-366

Intertemporal Equilibrium Theory: Indeterminacy, Bifurcations, and Stability

organized by Tapan Mitra and Kazuo Nishimura

Vol. 96, No. 1/2, February 2001

-

Introduction to Intertemporal Equilibrium Theory: Indeterminacy, Bifurcations, and Stability, Tapan Mitra and Kazuo Nishimura pp. 1-12

-

Growth Cycles and Market Crashes, Michele Boldrin and David K. Levine pp. 13-39

-

The Perils of Taylor Rules, Jess Benhabib, Stephanie Schmitt-Grohé and Martín Uribe pp. 40-69

-

Growth Dynamics and Returns to Scale: Bifurcation Analysis, Gaetano Antinolfi, Todd Keister and Karl Shell pp. 70-96

-

Chaotic Equilibrium Dynamics in Endogenous Growth Models, Michele Boldrin, Kazuo Nishimura, Tadashi Shigoka and Makoto Yano pp. 97-132

-

A Sufficient Condition for Topological Chaos with an Application to a Model of Endogenous Growth, Tapan Mitra pp. 133-152

-

A Spatial-Temporal Model of Human Capital Accumulation, Venkatesh Bala and Gerhard Sorger pp. 153-179

-

Optimal Environmental Management in the Presence of Irreversibilities, José Scheinkman and Thaleia Zariphopoulou pp. 180-207

-

On a Class of Stable Random Dynamical Systems: Theory and Applications, Rabi Bhattacharya and Mukul Majumdar pp. 208-229

-

Determinacy of Equilibrium in an Overlapping Generations Model with Heterogeneous Agents, Carine Nourry and Alain Venditti pp. 230-255

-

Discounting and Long-Run Behavior: Global Bifurcation Analysis of a Family of Dynamical Systems, Tapan Mitra and Kazuo Nishimura pp. 256-293

Political Economy

Vol. 94, No. 1, September 2000

-

Limits of Markets and Limits of Governments: An Introduction to a Symposium on Political Economy, V. V. Chari pp. 1-6

-

Large Poisson Games, Roger B. Myerson pp. 7-45

-

Government Turnover in Parliamentary Democracies, Daniel Diermeier and Antonio Merlo pp. 46-79

-

Political Power and the Credibility of Government Debt, Avinash Dixit and John Londregan pp. 80-105

-

The Economic Effects of Restrictions on Government Budget Deficits, Christian Ghiglino and Karl Shell pp. 106-137

Modeling Money and Studying Monetary Policy

organized by Neil Wallace

Vol. 81, No. 2, August 1998

-

Introduction to Modeling Money and Studying Monetary Policy, Neil Wallace pp. 223-231

-

Money Is Memory, Narayana R. Kocherlakota pp. 232-251

-

A Rudimentary Random-Matching Model with Divisible Money and Prices, Edward J. Green and Ruilin Zhou pp. 252-271

-

Incomplete Record-Keeping and Optimal Payment Arrangements, Narayana Kocherlakota and Neil Wallace pp. 272-289

-

Government Transaction Policy, Media of Exchange, and Prices, Yiting Li and Randall Wright pp. 290-313

-

Search for a Monetary Propagation Mechanism, Shouyong Shi pp. 314-352

-

Financial Market Frictions, Monetary Policy and Capital Accumulation in a Small Open Economy, Elisabeth Huybens and Bruce D. Smith pp. 353-400

-

Price Level Volatility: A Simple Model of Money Taxes and Sunspots, Joydeep Bhattacharya, Mark G. Guzman and Karl Shell pp. 401-430

-

Credible Monetary Policy in an Infinite Horizon Model: Recursive Approaches, Roberto Chang pp. 431-461

-

Expectation Traps and Discretion, V. V. Chari, Lawrence J. Christiano and Martin Eichenbaum pp. 462-492

Sunspots in Macroeconomics

organized by Jess Benhabib

Vol. 81, No. 1, July 1998

-

Introduction to Sunspots in Macroeconomics, Jess Benhabib pp. 1-6

-

Capacity Utilization under Increasing Returns to Scale, Yi Wen pp. 7-36

-

Fickle Consumers, Durable Goods, and Business Cycles, Mark Weder pp. 37-57

-

Indeterminacy and Sunspots with Constant Returns, Jess Benhabib and Kazuo Nishimura pp. 58-96

Market Psychology and Nonlinear Endogenous Business Cycles

organized by Jean-Michel Grandmont

-

Introduction to Market Psychology and Nonlinear Endogenous Business Cycles, Jean-Michel Grandmont pp. 1-13

-

Capital-Labor Substitution and Competitive Nonlinear Endogenous Business Cycles, Jean-Michel Grandmont, Patrick Pintus and Robin de Vilder pp. 14-59

-

Multiple Steady States and Endogenous Fluctuations with Increasing Returns to Scale in Production, Guido Cazzavillan, Teresa Lloyd-Braga and Patrick A. Pintus pp. 60-107

-

Correlation without Mediation: Expanding the Set of Equilibrium Outcomes by "Cheap" Pre-play Procedures, Elchanan Ben-Porath pp. 108-122

-

Aggregation, Determinacy, and Informational Efficiency for a Class of Economies with Asymmetric Information, Peter DeMarzo and Costis Skiadas pp. 123-152

-

On the Optimal Order of Natural Resource Use When the Capacity of the Inexhaustible Substitute Is Limited, Jean-Pierre Amigues, Pascal Favard, Gérard Gaudet and Michel Moreaux pp. 153-170

-

Partial Revelation with Rational Expectations, Aviad Heifetz and Heracles M. Polemarchakis pp. 171-181

Financial Market Innovation and Security Design

organized by Darrell Duffie and Rohit Rahii

Vol. 65, No. 1, February 1995

-

Financial Market Innovation and Security Design: An Introduction, Darrell Duffie and Rohit Rahi pp. 1-42

-

Welfare Effects of Financial Innovation in Incomplete Markets Economies with Several Consumption Goods, Ronel Elul pp. 43-78

-

Financial Innovation in a General Equilibrium Model and Wolfgang Pesendorfer pp. 79-116

-

Financial Innovation and Arbitrage Pricing in Frictional Economies, Zhiwu Chen pp. 117-135

-

Destructive Interference in an Imperfectly Competitive Multi-Security Market, Utpal Bhattacharya , Philip J. Reny and Matthew Spiegel pp. 136-170

-

Optimal Incomplete Markets with Asymmetric Information, Rohit Rahi pp. 171 -197

-

Endogenous Determination of the Degree of Market-Incompleteness in Futures Innovation, Kazuhiko Hashi pp. 198-217

-

Optimality of Incomplete Markets, Gabrielle Demange and Guy Laroque pp. 218-232

-

Private Information and the Design of Securities, Gabrielle Demange and Guy Laroque pp. 233-257

-

Commission-Revenue Maximization in a General Equilibrium Model of Asset Creation, Chiaki Hara pp. 258-298

Growth, Fluctuations, and Sunspots: Confronting the Data

organized by Jess Benhabib and Aldo Rustichini

Vol. 63, No. 1, June 1994

-

Introduction to the Symposium on Growth, Fluctuations, and Sunspots: Confronting the Data, Jess Benhabib and Aldo Rustichini pp. 1-18

-

Indeterminacy and Increasing Returns, Jess Benhabib and Roger E. A. Farmer pp. 19-41

-

Real Business Cycles and the Animal Spirits Hypothesis, Roger E. A. Farmer and Jang-Ting Guo pp. 42-72

-

Monopolistic Competition, Business Cycles, and the Composition of Aggregate Demand, Jordi Galí pp. 73-96

-

Divergence in Economic Performance: Transitional Dynamics with Multiple Equilibria, Danyang Xie pp. 97-112

-

Uniqueness and Indeterminacy: On the Dynamics of Endogenous Growth, Jess Benhabib and Roberto Perli pp. 113-142

Economic Growth: Theory and Computation

organized by Larry E. Jones and Nancy L. Stokey

Vol. 58, No. 2, December 1992

Introduction: Symposium on Economic Growth, Theory and Computations, Larry E. Jones and Nancy L. Stokey, pp.117-134

-

SAVINGS BEHAVIOR

-

Random Earnings Differences, Lifetime Liquidity Constraints, and Altruistic Intergenerational Transfers, John Laitner, pp. 135-170

-

-

Finite Lifetimes and Growth, Larry E. Jones and Rodolfo E. Manuelli, pp. 171-197

-

-

Dynamic Externalities, Multiple Equilibria, and Growth, Michele Boldrin, pp. 198-218

-

-

Communication, Commitment, and Growth, Albert Marcet and Ramon Marimon, pp. 219-249

-

POLICY ISSUES

-

Optimal Fiscal Policy in s Stochastic Growth Model, Xiaodong Zhu, pp. 250-289

-

-

Tax Distortions in a Neoclassical Monetary Economy, Thomas F. Cooley and Gary D. Hansen, pp. 290-316

-

HUMAN CAPITAL

-

Agricultural Productivity, Comparative Advantage, and economic Growth, Kiminori Matsuyama, pp. 317-334

-

-

The Last Shell Be First: Efficient Constraints on Foreign Borrowing in a Model of Endogenous Growth, Christophe Chamley, pp. 335-354

-

-

Efficient Equilibrium Convergence: Heterogeneity and Growth, Robert Tamura, pp. 355-376

-

-

In Search of Scale Effects in Trade and Growth, David K. Backus, Patrick J. Kehoe and Timothy J. Kehoe, pp. 377-409

Evolutionary Game Theory

organized by George J. Mailath

Vol. 57, No. 2, August 1992

-

Introduction: Symposium on Evolutionary Game Theory, George J. Mailath, pp. 259-277

-

Evolutionary Stability in Repeated Games Played by Finite Automata, Kenneth G. Binmore and Larry Samuelson, pp. 278-305

-

Evolutionary Stability with Equilibrium Entrants, Jeroen M. Swinkels, pp. 306-332

-

Evolution and Strategic Stability: From Maynard Smith to Kohlberg and Mertens, Jeroen M. Swinkels, pp. 333-342

-

Best Response Dynamics and Socially Stable Strategies, Akihiko Matsul, pp. 343-362

-

Evolutionary Stability in Asymmetric Games, Larry Samuelson and Jianbo Zhang, pp. 363-391

-

On the evolution of Optimizing Behavior, Eddie Dekel and Suzanne Scotchmer, pp. 392-406

-

On the Limit Points of Discrete Selection Dynamics, Antonio Cabrales and Joel Sobel, pp.407-419

-

Evolutionary Dynamics with Aggregate Shocks, D. Fudenberg and C. Harris, pp. 420-441

-

Average Behavior in Learning Models, David Canning, pp. 442-472

-

Laws of Large Numbers for Dynamical Systems with Randomly Matched Individuals, Richard T. Boylan, pp. 473-504

Noncooperative Bargaining

organized by Peter Linhart, Roy Radner and Mark Satterthwaite

Vol. 48, No. 1, June 1989

-

Introduction: Noncooperative Bargaining, Peter Linhart, Roy Radner and Mark Satterthwaite, pp. 1-17

-

A Direct Mechanism Characterization of Sequential Bargaining with One-Sided Incomplete Information, Lawrence M. Ausubel and Raymond J. Deneckere, pp. 18-46

-

Bargaining with Common Values, Daniel R. Vincent, pp. 47-62

-

Equilibria of the Sealed-Bid Mechanism for Bargaining with Incomplete Information, W. Leininger, P. B. Linhart and R. Radner, pp. 63-107

-

Bilateral Trade with the Sealed Bid k-Double Auction: Existence and Efficiency, Mark A. Satterthwaite, pp. 107-133

-

The Bilateral Monopoly Model: Approaching Certainty under the Split-the-Difference Mechanism, Elizabeth M. Broman, pp. 134-151

-

Minimax-Regret Strategies for Bargaining over Several Variables, P. B. Linhart and R. Radner, pp. 152-178

-

The Sealed-Bid Mechanism: An Experimental Study, Roy Radner and Andrew Schotter, pp. 179-220

-

Cheap Talk Can Matter in Bargaining, Joseph Farrell and Robert Gibbons, pp. 221-237

-

Pre-Play Communication in Two-Person Sealed-Bid Double Auctions, Steven A. Matthews and Andrew Postlewaite, pp. 238-263

-

Credible Negotiation Statements and Coherent Plans, Roger B. Myerson, pp. 264-303

-

The Rate at Which a Simple Market Converges to Efficiency as the Number of Traders Increases: An Asymptotic Result for Optimal Trading Mechanisms, Thomas A. Gresik and Mark A. Satterthwaite, pp. 304-332

Intertemporal Decentralization in Infinite Horizon Models

organized by Mukul Majumdar

Vol. 45, No. 2, August 1988

-

Decentralization in Infinite Horizon Economies: An Introduction, Mukul Majumdar, pp. 217-227

-

Optimal Inter-temporal Allocation Mechanisms and Decentralization of Decisions, Leonid Hurwicz, pp. 228-261

-

On Characterizing Optimal Competitive Programs in terms of Decentralizable Conditions, William A. Brock and Mukul Majumdar, pp. 262-273

-

Characterization of Intertemporal Optimality in Terms of Decentralizable Conditions: The Discounted Case, Swapan Dasgupta and Tapan Mitra, pp. 274-287

-

Intertemporal Optimality in a Closed Linear Model of Production, Swapan Dasgupta and Tapan Mitra, pp. 288-315

-

On Characterizing Optimality of Stochastic Competitive Processes, Yaw Nyarko, pp. 316-329

Nonlinear Economic Dynamics

organized by Jean-Michel Grandmont

Vol. 40, No. 1, October 1986

-

Introduction, Jean-Michel Grandmont and Pierre Malgrange, pp. 3-12

-

Competitive Chaos, Raymond Deneckere and Steve Pelikan, pp. 13-25

-

On the Indeterminacy of Capital Accumulation Paths, Michele Boldrin and Luigi Montrucchio, pp. 26-39

-

Dynamic Complexity ion Duopoly Games, Rose-Anna Dana and Luigi Montrucchio, pp. 40-56

-

Stabilizing Competitive Business Cycles, Jean-Michel Grandmont, pp. 57-76

-

Deficits and Cycles, Roger E. A. Farmer, pg. 77-88

-

Equilibrium Cycles in an Overlapping Generations Economy with Production, Pietro Reichlin, pp. 89-102

-

Stationary Sunspot Equilibria in an N Commodity World, Roger Guesnerie, pp. 103-127

-

Stationary Sunspot Equilibria in a Finance Constrained Economy, Michael Woodford, pp. 128-137

-

Stability of Cycles and Expectations, Jean-Michel Grandmont and Guy Laroque, pp.138-151

-

On the Local Convergence of Economic Mechanisms, Donald G. Saari and Steven R. Williams, pp. 152-167

-

Distinguishing Random and Deterministic Systems: Abridged Version, W. A. Brock, pp. 168-195

Strategic Behavior and Competition

organized by Ehud Kalai

Vol. 39, No. 1, June 1986

Strategic Behavior and Competition: An Overview, Ehud Kalai, pp. 1-13

Equilibrium, Decentralization and Differential Information

-

Implementation in Differential Information Economics, Andrew Postlewaite and David Schmeidler, pp. 14-33

-

Private Information in Large Economics, Thomas R. Palfrey and Sanjay Srivastava, pp. 34- 58

-

The Scope of the Hypothesis of Bayesian Equilibrium, John O. Ledyard, pp. 59-82

Rationality, Equilibrium Notions, Cooperation and Bargaining

-

Finite Automata Play the Repeated Prisoner’s Dilemma, Ariel Rubinstein, pp. 83-96

-

Perfect Sequential Equilibrium, Sanford J. Grossman and Motty Perry, pp. 97-119

-

Sequential Bargaining under Asymmetric Information, Sanford J. Grossman, pp. 120-154

-

Foundations of Dynamic Monopoly and the Coase Conjecture, Faruk Gul, Hugo Sonnenschein and Robert Wilson, pp. 155-190

Dynamic Oligopolistic Competition

-

Extremal Equibria of Oligopolistic Supergames, Dilip Abreu, pp. 191-225

-

Subgame Perfect Reaction Function Equilibria in Discounted Duopoly Supergames Are Trivial, William G. Stanford, pp. 226-232

-

On Continuous Reaction Function Equilibria in Duopoly Supergames with Mean Payoffs, William G. Stanford, pp. 233-250

-

Optimal Cartel Equilibria with Imperfect Monitoring, Dilip Abreu, David Pearce and Ennio Stacchetti, pp.251-269

Reputations in Finitely Repeated Games

organized by David M. Kreps, Paul Milgrom, John Roberts and Robert Wilson

Vol. 27, No. 2, August 1982

-

Rational Cooperation in the Finitely Repeated Prisoners’ Dilemma, David M. Kreps, Paul Milgrom, John Roberts and Robert Wilson, pp. 245-252

-

Reputation and Imprefect Information, David M. Kreps and Robert Wilson, pp. 253-279

-

Predation, Reputation and Entry Deterrence, Paul Milgrom and John Roberts, pp. 280-312

Rational Expectations in Microeconomic Models

organized by James S. Jordan and Roy Radner

Vol. 26, No. 2, April 1982

-

Rational Expectations in Microeconomic Models: An Overview, James S. Jordan and Roy Radner, pp. 201-223

-

The Generic Existence of Rational Expectations Equilibrium in the Higher Dimensional Case, J. S. Jordan, pp. 224-243

-

Approximate Equilibria in Microeconomic Rational Expectations Models, Beth Allen, pp. 244-260

-

On the Existence of rational Expectations Equilibrium, Robert M. Anderson and Hugo Sonnenschein, pp.261-278

-

Expectations Equilibrium with Conditioning on Part Prices: A Mean-Variance Example, Martin F. Hellwig, pp. 279-312

-

Introduction to the Stability of Rational Expectations Equilibrium, L.E. Blume, M.M. Bray and D. Easley, pp. 313-317

-

Learning, Estimation and the Stability of Rational Expectations, Margaret Bray, pp. 318-339

-

Learning to Be Rational, Lawrence E. Blume and David Easley, pp. 340-351

Non-Cooperative approaches to the Theory of Perfect Competition

organized by Andreu Mas-Colell

Vol. 22, No. 2, April 1980

-

Non-Cooperative approaches to the Theory of Perfect Competition: Presentation, Andreu Mas-Colell, pp.121-135

-

Collusive Behavior in Noncooperative Epsilon-Equilibria of Oligopolies with Long but Finite Lives, Roy Radner, pp.136-154

-

Noncooperative Price Taking in Large Dynamic Markets, Edward J. Green, pp. 155-182

-

The No-Surplus Condition as a Characterization of Perfectly Competitive Equilibrium, Joseph M. Ostroy, pp. 183-207

-

A Characterization of Perfectly Competitive Economies with Production, Louis Makowski, pp. 208-221

-

Perfect Competition, the Profit Criterion and the Organization of Economic Activity, Louis Makowski, pp. 222-242

-

Small efficient Scale as a Foundation for Walrasian Equilibrium, William Novshek and Hugo Sonnenschein, pp. 243-255

-

The Limit Points of Monopolistic Competition, Kevin Roberts, pp. 256-278

-

Perfect Competition and Optimal Product Differentiation, Oliver D. Hart, pp. 279-312

-

Equilibrium in Simple Spatial (or Differentiated Product) Models, William Novshek, pp. 313-326

-

Entry (and Exit) in a Differentiated Industry, J. Jaskold Gabszewicz and J.F. Thisse, pp. 327-338

-

Efficiency Properties of Strategic Market Games: An Axiomatic Approach, Pradeep Dubey, Andreu Mas-Colell and Martin Shubik, pp. 339-362

-

Nash Equilibria of Market Games: Finiteness and Inefficiency, Pradeep Dubey, pp. 363-376

Hamiltonian Dynamics in Economics

organized by David Cass and Karl Shell

Vol. 12, No. 1, February 1976

-

Introduction to Hamiltonian Dynamics in Economics, David Cass and Karl Shell, pp. 1-10

-

On Optimal Steady States of n-Sector Growth Models when utility is Discounted, Jose´ A. Scheinkman, pp. 11-30

-

The Structure and Stability of Competitive Dynamical Systems, David Cass and Karl Shell, pp. 31-70

-

Saddle Points of Hamiltonian Systems in Convex Lagrange Problems Having a Nonzero Discount Rate, R. Tyrrell Rockafellar, pp. 71-113

-

Existence of Solutions to Hamiltonian Dynamical Systems of Optimal Growth, Robert E. Gaines, pp. 114-130

-

A Characterization of the Normalized Restricted Profit Function, Lawrence J. Lau, pp 131-163

-

Global Asymptotic Stability of Optimal Control Systems with Applications to the Theory of Economic Growth, William A. Brock and Jose´A. Scheinkman, pp. 164-190

-

A Growth Property in Concave-Convex Hamiltonian Systems, R. Tyrrell Rockafellar, pp. 191-196

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Theorie de la connaissance

12/08/2012 18:15

biologie

38

Pour conclure, il me semble que les modèles neutres de l’évolution culturelle et

les modèles de reconstruction phylogénétiques offrent des outils essentiels pour l’étude

de l’évolution culturelle. Ces outils sont cependant encore peu développés et manquent

. Par exemple dans le cas des manuscrits du ‘Canterbury tale’ (Barbrook,

Howe, Blake, & Robinson, 1998) ou encore dans le cas de motifs textiles (Tehrani &

Collard, 2002). Ces méthodes ont provoqués de vifs débats autour de ce que pouvaient

mettre en évidence ces résultats (Borgerhoff Mulder, 2001; Boyd, Richerson,

Borgerhoff Mulder, & Durham, 1997; Eerkens, Bettinger, & McElreath, 2006; Mace &

Holden, 2005; O'Brien & Lyman, 2003b). Les limites de l’approche phylogénétiques

sont résumés ainsi par Monique Borgerhoff Mulder :

The view that human history can be captured through the construction of

phylogenies is controversial for several reasons. First, unlike species phylogenies, where

each has a pretty clear hierarchical relationship to the others on account of most of its DNA

having been channeled through the same history, within-species phylogenies exhibit no

unique branching among units, be these individuals or populations. Second, humans have

extraordinary capacities for the horizontal transmission of cultural traits, between as well as

within groups, with elaborate systems of communication allowing for borrowing, learning,

exchange, imitation, stealing, and even imposition of traits between societies. Third, cultural

transmission fosters high rates of innovation, permitting rapid evolutionary change. Fourth,

cultural transmission does not preclude recombination, whereby merging groups combine

elements of each, a classic example being the Ariaal, a fusion of northern Kenyan Samburu

and Rendille pastoralists. It is therefore not only very difficult to reconstruct accurate

phylogenies of human cultural traits, but questionable that a single phylogeny captures

much of a group’s history. (Borgerhoff Mulder, 2001)

Cependant, d’une part plusieurs phylogénies culturelles ont été réalisées avec succès,

d’autre part on s’attend à ce que les reconstructions phylogénétiques soient plus ou

moins délicates, voir impossibles, en fonction des éléments culturels étudiés (de la

même manière qu’en biologie les reconstructions phylogénétiques sont plus ou moins

délicates en fonction des groupes étudiés). A terme, l’importance des méthodes

phylogénétiques dans le domaine culturel s’évaluera par le nombre d’études réussies et

celui-ci dépendra en grande partie de la possibilité d’adapter les méthodes

phylogénétiques aux cas culturels, donc en grande partie de notre connaissance des

mécanismes de transmission de la culture.

38 Nous ne parlerons pas ici des méthodes phylogénétiques appliquées au langage.

L

ES FORCES LIEES AU CONTENU DES ELEMENTS CULTURELS

La variation guidée correspond au fait que les individus peuvent modifier des

éléments culturels qu’ils ont acquis et les transmettre à d’autres personnes par la suite.

Dans le milieu scientifique par exemple, il arrive fréquemment qu’un scientifique publie

une théorie, que celle-ci soit reprise, modifiée et publiée sous une forme légèrement

différente par un autre scientifique, que cette dernière version soit elle-même reprise et

modifiée et ainsi de suite. Il s’agit d’un exemple du processus de variation guidée. Les

individus utilisent les éléments culturels précédents pour en créer de nouveaux, non pas

de manière purement aléatoire mais dans une direction donnée (pour trouver une théorie

qui rende mieux compte des faits dans le cas scientifique). D’autres exemples évidents

concernent les différentes versions des logiciels informatiques, les articles des

encyclopédies libres comme Wikipédia, et de nombreuses innovations technologiques.

Dans chacun de ces cas, l’évolution des éléments culturels considérés repose sur 1)

l’acquisition des éléments précédents, 2) leur modification dans une direction donnée et

3) la transmission de ces éléments modifiés.

Conséquences sur l’évolution culturelle

Pour modéliser les conséquences de la variation guidée sur l’évolution culturelle,

Boyd et Richerson (1985) proposent un modèle équivalent au suivant : imaginez que

l’on observe l’évolution des techniques de pêche d’une population insulaire isolée.

Appelons

i x la technique utilisée par l’individu i ( i∈[1, N]) au temps t et '

i

x

la

technique utilisée par le même individu au temps t+1. Boyd et Richerson font

l’hypothèse qu’il existe une technique optimale que les individus cherchent à atteindre

et qui dépend de la situation, appelons-la

0 P . La force de variation guidée correspond au

fait que les individus, entre deux pas de temps, observent les techniques utilisée par les

autres individus de la population et génèrent de nouvelles techniques qui

en moyenne

sont biaisées vers la technique optimale. Ce modèle est équivalent à celui que nous

avons proposé dans notre étude de la fidélité de l’imitation (voir l’équation 2.1). Pour

tel-00431055

continuer dans le même esprit, nous appellerons contribution causale sociale la partie de

l’élément culturel qui est transmise entre les individus et contribution causale

individuelle la partie modifiée par l’individu

39

'

(1 ) i i i x = fS + − f P

. On peut représenter la variation guidée

en prenant l’équation suivante (identique à 2.1) :

(3.1)

Dans cette équation

i S représente la contribution causale sociale et i P la contribution

individuelle.

f est un coefficient qui détermine l’importance relative des facteurs

sociaux et individuels dans la formation des nouvelles techniques. Si

f =1 par exemple,

les facteurs individuels n’ont aucun rôle et la technique n’évolue pas. Si

f = 0 , les

facteurs sociaux n’ont aucun rôle. Si l’on suppose que la transmission sociale est non

biaisée,

E(S) = x , et qu’en moyenne les transformations tendent vers la technique

optimale,

0 E(P) = P , dans le cas général où f ne vaut ni 0, ni 1, si l’on calcule le

changement moyen entre deux générations (équivalente à l’équation 2.2), on a :

0

Δx = (1− f )(P − x) (3.2)

Cette équation est identique à celle trouvée précédemment et dans ce cas, il est clair que

très rapidement la technique utilisée converge vers la forme optimale

0 P . Autrement dit,

si tous les individus modifient progressivement un élément culturel dans une direction

donnée, très rapidement cet élément prend la forme désirée. On retrouve ici le résultat

que nous avons obtenu dans le cas de l’imitation.

Evolution

Boyd et Richerson cherchent ensuite à établir sous quelles conditions

l’émergence de la variation guidée peut être favorisée par sélection naturelle par rapport

à un apprentissage purement individuel. Dans notre exemple, si la quantité de poissons

ramenés par les pêcheurs influence la fitness des pêcheurs, la méthode d’apprentissage

qui permet d’acquérir la technique la plus proche de la technique optimale va être

39 La contribution causale sociale correspond à ce qui a été appelé apprentissage social par Boyd et

Richerson et la contribution causale individuelle correspond à l’apprentissage individuel ou par essais et

erreurs. Comme il ne s’agira pas toujours d’apprentissage à proprement parler je préfère garder une

dénomination neutre vis-à-vis des mécanismes impliqués dans la production des éléments culturels.

favorisée par sélection naturelle. Pour étudier ces effets, ils comparent deux gènes, un

qui repose légèrement plus sur l’apprentissage individuel que l’autre (c’est-à-dire qui est

un peu moins fidèle dans notre modèle, qui a une valeur de

f plus faible), et cherchent

sous quelles conditions l’un ou l’autre des deux gènes est favorisé par sélection

naturelle.

Boyd et Richerson montrent que pour que la variation guidée évolue il faut que

le taux d’erreur lié aux facteurs individuels soit plus élevé que celui lié aux facteurs

sociaux. En effet, si la technique utilisée est entièrement déterminée par des facteurs

individuels (

f = 0 ), et que ceux-ci produisent de nombreuses erreurs (la variance de i P

est élevée), peu d’individus utilisent la technique optimale. Ce qui revient à dire que si

tous les pêcheurs apprennent à pêcher uniquement par eux-mêmes, il y a peu de

pêcheurs qui utilisent la technique optimale. Dans ce cas, c’est la distribution des

erreurs liées aux facteurs individuels qui détermine la fitness moyenne de la population.

Si on suppose au contraire que

f =1, c'est-à-dire si la technique est déterminée

entièrement par les facteurs sociaux, et si

0 x = P , c’est-à-dire qu’en moyenne la

technique utilisée est optimale, alors c’est la distribution des erreurs liées aux facteurs

sociaux qui déterminent la fitness moyenne de la population (la variance de

i S ).

Autrement dit, si les pêcheurs apprennent à pêcher uniquement en observant leurs

collègues et qu’ils n’arrivent pas à imiter correctement leur technique alors peu de

pêcheurs utilisent la technique optimale.

Les autres résultats de Boyd et Richerson peuvent s’analyser en termes du

rapport entre les erreurs liées aux facteurs individuels et celles liées aux facteurs sociaux.

Dans un environnement constant et homogène par exemple, la sélection génétique

favorise l’apprentissage social si le taux d’erreurs par apprentissage individuel est élevé.

Autrement dit, si les champignons qui poussent en forêt sont toujours les mêmes, et

étant donné qu’il en existe de nombreux qui sont toxiques, la sélection naturelle favorise

l’émergence d’une capacité d’apprentissage qui repose essentiellement sur le

comportement des autres, pas sur un mécanisme d’essais et erreurs qui produit souvent

des erreurs mortelles. Si au contraire l’environnement est constant et que le mécanisme

d’apprentissage individuel ne produit pas d’erreur, alors la sélection naturelle favorise

ce dernier mécanisme. Dans un environnement hétérogène, si, par exemple, différentes

îles sont reliées entre elles par des phénomènes de migration et qu’à chaque île

tel-00431055

| |

|

|

|

|